3

Essential Questions:

- What are techniques used by companies to select and train their employees?

- How are evaluations of employees conducted?

- What are legal requirements companies must follow in selection, hiring, training and promotion?

- What are the core elements of the communication process, including verbal and nonverbal components? Why is this important?

- What are the barriers to effective communication?

Selecting Employees

When you read job advertisements, do you ever wonder how the company comes up with the job description? Often, this is done with the help of I-O psychologists. There are two related but different approaches to job analysis — you may be familiar with the results of each as they often appear on the same job advertisement. The first approach is task-oriented and lists in detail the tasks that will be performed for the job. Each task is typically rated on scales for how frequently it is performed, how difficult it is, and how important it is to the job. The second approach is worker-oriented. This approach describes the characteristics required of the worker to successfully perform the job. This second approach has been called job specification (Dierdorff & Wilson, 2003). For job specification, the knowledge, skills, and abilities (KSAs) that the job requires are identified.

Observation, surveys, and interviews are used to obtain the information required for both types of job analysis. It is possible to observe someone who is proficient in a position and analyze what skills are apparent. Another approach used is to interview people presently holding that position, their peers, and their supervisors to get a consensus of what they believe are the requirements of the job.

How accurate and reliable is a job analysis? Research suggests that it can depend on the nature of the descriptions and the source for the job analysis. For example, Dierdorff & Wilson (2003) found that job analyses developed from descriptions provided by people holding the job themselves were the least reliable; however, they did not study or speculate why this was the case.

The United States Department of Labor maintains a database of previously compiled job analyses for different jobs and occupations. This allows the I-O psychologist to access previous analyses for nearly any type of occupation. This system is called O*Net (accessible at www.online.onetcenter.org). The site is open and you can see the KSAs that are listed for your own position or one you might be curious about. Each occupation lists the tasks, knowledge, skills, abilities, work context, work activities, education requirements, interests, personality requirements, and work styles that are deemed necessary for success in that position. You can also see data on average earnings and projected job growth in that industry.

The O*Net database describes the skills, knowledge, and education required for occupations, as well as what personality types and work styles are best suited to the role. See what it has to say about being a food server in a restaurant or an elementary school teacher or an industrial-organizational psychologist.

Candidate Analysis and Testing

Once a company identifies potential candidates for a position, the candidates’ knowledge, skills, and other abilities must be evaluated and compared with the job description. These evaluations can involve testing, an interview, and work samples or exercises. You learned about personality tests in the chapter on personality; in the I-O context, they are used to identify the personality characteristics of the candidate in an effort to match those to personality characteristics that would ensure good performance on the job. For example, a high rating of agreeableness might be desirable in a customer support position. However, it is not always clear how best to correlate personality characteristics with predictions of job performance. It might be that too high of a score on agreeableness is actually a hindrance in the customer support position. For example, if a customer has a misperception about a product or service, agreeing with their misperception will not ultimately lead to resolution of their complaint. Any use of personality tests should be accompanied by a verified assessment of what scores on the test correlate with good performance (Arthur, Woehr, & Graziano, 2001). Other types of tests that may be given to candidates include IQ tests, integrity tests, and physical tests, such as drug tests or physical fitness tests.

Training

Training is an important element of success and performance in many jobs. Most jobs begin with an orientation period during which the new employee is provided information regarding the company history, policies, and administrative protocols such as time tracking, benefits, and reporting requirements. An important goal of orientation training is to educate the new employee about the organizational culture, the values, visions, hierarchies, norms and ways the company’s employees interact — essentially how the organization is run, how it operates, and how it makes decisions. There will also be training that is specific to the job the individual was hired to do, or training during the individual’s period of employment that teaches aspects of new duties, or how to use new physical or software tools. Much of these kinds of training will be formalized for the employee; for example, orientation training is often accomplished using software presentations, group presentations by members of the human resources department or with people in the new hire’s department (Figure 1).

Mentoring is a form of informal training in which an experienced employee guides the work of a new employee. In some situations, mentors will be formally assigned to a new employee, while in others a mentoring relationship may develop informally.

Mentoring effects on the mentor and the employee being mentored, the protégé, have been studied in recent years. In a review of mentoring studies, Eby, Allen, Evans, Ng, & DuBois (2008) found significant but small effects of mentoring on performance (i.e., behavioral outcomes), motivation and satisfaction, and actual career outcomes. In a more detailed review, Allen, Eby, Poteet, Lentz, & Lima (2004) found that mentoring positively affected a protégé’s compensation and number of promotions compared with non-mentored employees. In addition, protégés were more satisfied with their careers and had greater job satisfaction. All of the effects were small but significant. Eby, Durley, Evans, & Ragins (2006) examined mentoring effects on the mentor and found that mentoring was associated with greater job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Gentry, Weber, & Sadri (2008) found that mentoring was positively related with performance ratings by supervisors. Allen, Lentz, & Day (2006) found in a comparison of mentors and non-mentors that mentoring led to greater reported salaries and promotions.

Mentoring is recognized to be particularly important to the career success of women (McKeen & Bujaki, 2007) by creating connections to informal networks, adopting a style of interaction that male managers are comfortable with, and with overcoming discrimination in job promotions.

Gender combinations in mentoring relationships are also an area of active study. Ragins & Cotton (1999) studied the effects of gender on the outcomes of mentoring relationships and found that protégés with a history of male mentors had significantly higher compensation especially for male protégés. The study found that female mentor–male protégé relationships were considerably rarer than the other gender combinations.

In an examination of a large number of studies on the effectiveness of organizational training to meet its goals, Arthur, Bennett, Edens, and Bell (2003) found that training was, in fact, effective when measured by the immediate response of the employee to the training effort, evaluation of learning outcomes (e.g., a test at the end of the training), behavioral measurements of job activities by a supervisor, and results-based criteria (e.g., productivity or profits). The examined studies represented diverse forms of training including self-instruction, lecture and discussion, and computer assisted training.

Evaluating Employees

Industrial and organizational psychologists are typically involved in designing performance-appraisal systems for organizations. These systems are designed to evaluate whether each employee is performing her job satisfactorily. Industrial and organizational psychologists study, research, and implement ways to make work evaluations as fair and positive as possible; they also work to decrease the subjectivity involved with performance ratings. Fairly evaluated work helps employees do their jobs better, improves the likelihood of people being in the right jobs for their talents, maintains fairness, and identifies company and individual training needs.

Performance appraisals are typically documented several times a year, often with a formal process and an annual face-to-face brief meeting between an employee and his supervisor. It is important that the original job analysis play a role in performance appraisal as well as any goals that have been set by the employee or by the employee and supervisor. The meeting is often used for the supervisor to communicate specific concerns about the employee’s performance and to positively reinforce elements of good performance. It may also be used to discuss specific performance rewards, such as a pay increase, or consequences of poor performance, such as a probationary period. Part of the function of performance appraisals for the organization is to document poor performance to bolster decisions to terminate an employee.

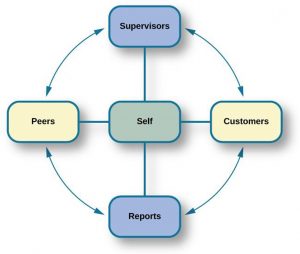

Performance appraisals are becoming more complex processes within organizations and are often used to motivate employees to improve performance and expand their areas of competence, in addition to assessing their job performance. In this capacity, performance appraisals can be used to identify opportunities for training or whether a particular training program has been successful. One approach to performance appraisal is called 360-degree feedback appraisal (Figure 2). In this system, the employee’s appraisal derives from a combination of ratings by supervisors, peers, employees supervised by the employee, and from the employee herself. Occasionally, outside observers may be used as well, such as customers. The purpose of 360-degree system is to give the employee (who may be a manager) and supervisor different perspectives of the employee’s job performance; the system should help employees make improvements through their own efforts or through training. The system is also used in a traditional performance-appraisal context, providing the supervisor with more information with which to make decisions about the employee’s position and compensation (Tornow, 1993a).

Few studies have assessed the effectiveness of 360-degree methods, but Atkins and Wood (2002) found that the self and peer ratings were unreliable as an assessment of an employee’s performance and that even supervisors tended to underrate employees that gave themselves modest feedback ratings. However, a different perspective sees this variability in ratings as a positive in that it provides for greater learning on the part of the employees as they and their supervisor discuss the reasons for the discrepancies (Tornow, 1993b).

In theory, performance appraisals should be an asset for an organization wishing to achieve its goals, and most employees will actually solicit feedback regarding their jobs if it is not offered (DeNisi & Kluger, 2000). However, in practice, many performance evaluations are disliked by organizations, employees, or both (Fletcher, 2001), and few of them have been adequately tested to see if they do in fact improve performance or motivate employees (DeNisi & Kluger, 2000). One of the reasons evaluations fail to accomplish their purpose in an organization is that performance appraisal systems are often used incorrectly or are of an inappropriate type for an organization’s particular culture (Schraeder, Becton, & Portis, 2007). An organization’s culture is how the organization is run, how it operates, and how it makes decisions. It is based on the collective values, hierarchies, and how individuals within the organization interact. Examining the effectiveness of performance appraisal systems in particular organizations and the effectiveness of training for the implementation of the performance appraisal system is an active area of research in industrial psychology (Fletcher, 2001).

Bias and Protections in Hiring

In an ideal hiring process, an organization would generate a job analysis that accurately reflects the requirements of the position, and it would accurately assess candidates’ KSAs to determine who the best individual is to carry out the job’s requirements. For many reasons, hiring decisions in the real world are often made based on factors other than matching a job analysis to KSAs. As mentioned earlier, interview rankings can be influenced by other factors: similarity to the interviewer (Bye, Horverak, Sandal, Sam, & Vijver, 2014) and the regional accent of the interviewee (Rakić, Steffens, & Mummendey 2011). A study by Agerström & Rooth (2011) examined hiring managers’ decisions to invite equally qualified normal-weight and obese job applicants to an interview. The decisions of the hiring managers were based on photographs of the two applicants. The study found that hiring managers that scored high on a test of negative associations with overweight people displayed a bias in favor of inviting the equally qualified normal-weight applicant but not inviting the obese applicant. The association test measures automatic or subconscious associations between an individual’s negative or positive values and, in this case, the body-weight attribute. A meta-analysis of experimental studies found that physical attractiveness benefited individuals in various job-related outcomes such as hiring, promotion, and performance review (Hosoda, Stone-Romero, & Coats, 2003). They also found that the strength of the benefit appeared to be decreasing with time between the late 1970s and the late 1990s.

Some hiring criteria may be related to a particular group an applicant belongs to and not individual abilities. Unless membership in that group directly affects potential job performance, a decision based on group membership is discriminatory (Figure 3). To combat hiring discrimination, in the United States there are numerous city, state, and federal laws that prevent hiring based on various group-membership criteria. For example, did you know it is illegal for a potential employer to ask your age in an interview? Did you know that an employer cannot ask you whether you are married, a U.S. citizen, have disabilities, or what your race or religion is? They cannot even ask questions that might shed some light on these attributes, such as where you were born or who you live with. These are only a few of the restrictions that are in place to prevent discrimination in hiring. In the United States, federal anti-discrimination laws are administered by the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC).

The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC)

The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) is responsible for enforcing federal laws that make it illegal to discriminate against a job applicant or an employee because of the person’s race, color, religion, sex (including pregnancy), national origin, age (40 or older), disability, or genetic information. Figure 4 provides some of the legal language from laws that have been passed to prevent discrimination.

The United States has several specific laws regarding fairness and avoidance of discrimination. The Equal Pay Act requires that equal pay for men and women in the same workplace who are performing equal work. Despite the law, persistent inequities in earnings between men and women exist. Corbett & Hill (2012) studied one facet of the gender gap by looking at earnings in the first year after college in the United States. Just comparing the earnings of women to men, women earn about 82 cents for every dollar a man earns in their first year out of college. However, some of this difference can be explained by education, career, and life choices, such as choosing majors with lower earning potential or specific jobs within a field that have less responsibility. When these factors were corrected the study found an unexplained seven-cents-on-the-dollar gap in the first year after college that can be attributed to gender discrimination in pay. This approach to analysis of the gender pay gap, called the human capital model, has been criticized. Lips (2013) argues that the education, career, and life choices can, in fact, be constrained by necessities imposed by gender discrimination. This suggests that removing these factors entirely from the gender gap equation leads to an estimate of the size of the pay gap that is too small.

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 makes it illegal to treat individuals unfavorably because of their race or color of their skin: An employer cannot discriminate based on skin color, hair texture, or other immutable characteristics, which are traits of an individual that are fundamental to her identity, in hiring, benefits, promotions, or termination of employees (Figure 4). The Pregnancy Discrimination Act of 1978 amends the Civil Rights Act; it prohibits job (e.g., employment, pay, and termination) discrimination of a woman because she is pregnant as long as she can perform the work required.

The Supreme Court ruling in Griggs v. Duke Power Co. made it illegal under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act to include educational requirements in a job description (e.g., high school diploma) that negatively impacts one race over another if the requirement cannot be shown to be directly related to job performance. The EEOC (2014) received more than 94,000 charges of various kinds of employment discrimination in 2013. Many of the filings are for multiple forms of discrimination and include charges of retaliation for making a claim, which itself is illegal. Only a small fraction of these claims become suits filed in a federal court, although the suits may represent the claims of more than one person. In 2013, there were 148 suits filed in federal courts.

Federal legislation does not protect employees in the private sector from discrimination related to sexual orientation and gender identity. These groups include lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals. There is evidence of discrimination derived from surveys of workers, studies of complaint filings, wage comparison studies, and controlled job-interview studies (Badgett, Sears, Lau, & Ho, 2009). Federal legislation protects federal employees from such discrimination; the District of Columbia and 20 states have laws protecting public and private employees from discrimination for sexual orientation (American Civil Liberties Union, n.d). Most of the states with these laws also protect against discrimination based on gender identity. Gender identity, as discussed when you learned about sexual behavior, refers to one’s sense of being male or female.

Many cities and counties have adopted local legislation preventing discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity (Human Rights Campaign, 2013a), and some companies have recognized a benefit to explicitly stating that their hiring must not discriminate on these bases (Human Rights Campaign, 2013b).

Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA)

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990 states people may not be discriminated against due to the nature of their disability. A disability is defined as a physical or mental impairment that limits one or more major life activities such as hearing, walking, and breathing. An employer must make reasonable accommodations for the performance of a disabled employee’s job. This might include making the work facility handicapped accessible with ramps, providing readers for blind personnel, or allowing for more frequent breaks. The ADA has now been expanded to include individuals with alcoholism, former drug use, obesity, or psychiatric disabilities. The premise of the law is that disabled individuals can contribute to an organization and they cannot be discriminated against because of their disabilities (O’Keefe & Bruyere, 1994).

The Civil Rights Act and the Age Discrimination in Employment Act make provisions for bona fide occupational qualifications (BFOQs), which are requirements of certain occupations for which denying an individual employment would otherwise violate the law. For example, there may be cases in which religion, national origin, age, and sex are bona fide occupational qualifications. There are no BFOQ exceptions that apply to race, although the first amendment protects artistic expressions, such as films, in making race a requirement of a role. Clearcut examples of BFOQs would be hiring someone of a specific religion for a leadership position in a worship facility, or for an executive position in religiously affiliated institutions, such as the president of a university with religious ties. Age has been determined to be a BFOQ for airline pilots; hence, there are mandatory retirement ages for safety reasons. Sex has been determined as a BFOQ for guards in male prisons.

Sex (gender) is the most common reason for invoking a BFOQ as a defense against accusing an employer of discrimination (Manley, 2009). Courts have established a three-part test for sex-related BFOQs that are often used in other types of legal cases for determining whether a BFOQ exists. The first of these is whether all or substantially all women would be unable to perform a job. This is the reason most physical limitations, such as “able to lift 30 pounds,” fail as reasons to discriminate because most women are able to lift this weight. The second test is the “essence of the business” test, in which having to choose the other gender would undermine the essence of the business operation. This test was the reason the now defunct Pan American World Airways (i.e., Pan Am) was told it could not hire only female flight attendants. Hiring men would not have undermined the essence of this business. On a deeper level, this means that hiring cannot be made purely on customers’ or others’ preferences. The third and final test is whether the employer cannot make reasonable alternative accommodations, such as re-assigning staff so that a woman does not have to work in a male-only part of a jail or other gender-specific facility. Privacy concerns are a major reason why discrimination based on gender is upheld by the courts, for example in situations such as hires for nursing or custodial staff (Manley, 2009). Most cases of BFOQs are decided on a case-by-case basis and these court decisions inform policy and future case decisions.

The restaurant chain Hooters, which hires only female wait staff and has them dress in a sexually provocative manner, is commonly cited as a discriminatory employer. The chain would argue that the female employees are an essential part of their business in that they market through sex appeal and the wait staff attract customers (Figure 5). Men have filed discrimination charges against Hooters in the past for not hiring them as wait staff simply because they are men. The chain has avoided a court decision on their hiring practices by settling out of court with the plaintiffs in each case. Do you think their practices violate the Civil Rights Act? See if you can apply the three court tests to this case and make a decision about whether a case that went to trial would find in favor of the plaintiff or the chain.

Communication Essentials

The ability to effectively communicate is a necessary condition for successfully planning, organizing, leading, and controlling. Communication is vital to organizations — it’s how we coordinate actions and achieve goals. It is defined in the Merriam-Webster’s dictionary as “a process by which information is exchanged between individuals through a common system of symbols, signs, or behavior (Merriam-Webster, 2008).” We know that 50%–90% of a manager’s time is spent communicating (Schnake, et. al., 1990) and that communication ability is related to a manager’s performance (Penley, et. al., 1991). In most work environments, a miscommunication is an annoyance — it can interrupt workflow by causing delays and interpersonal strife. And in some work arenas, like operating rooms and airplane cockpits, communication can be a matter of life and death.

For leaders and organizations, poor communication costs money and wastes time. One study found that 14% of each workweek is wasted on poor communication (Armour, 1998). In contrast, effective communication is an asset for organizations and individuals alike. Effective communication skills, for example, are an asset for job seekers. A recent study of recruiters at 85 business schools ranked communication and interpersonal skills as the highest skills they were looking for, with 89% of the recruiters saying they were important (Alsop, 2006). Good communication can also help a company retain its star employees. Surveys find that when employees think their organizations do a good job of keeping them informed about matters that affect them and they have ready access to the information they need to do their jobs, they are more satisfied with their employers (Mercer, 2003). So, can good communication increase a company’s market value? The answer seems to be yes. “When you foster ongoing communications internally, you will have more satisfied employees who will be better equipped to effectively communicate with your customers,” says Susan Meisinger, President/CEO of the Society for Human Resource Management, citing research findings that for organizations that are able to improve their communication integrity, their market value increases by as much as 7.1% (Meisinger, 2003). We will explore the definition and benefits of effective communication in our next section.

The Communication Process

Communication fulfills three main functions within an organization: (1) transmitting information, (2) coordinating effort, and (3) sharing emotions and feelings. All these functions are vital to a successful organization. Transmitting information is vital to an organization’s ability to function. Coordinating effort within the organization helps people work toward the same goals. Sharing emotions and feelings bonds teams and unites people in times of celebration and crisis. Effective communication helps people grasp issues, build rapport with coworkers, and achieve consensus. So, how can we communicate effectively? The first step is to understand the communication process.

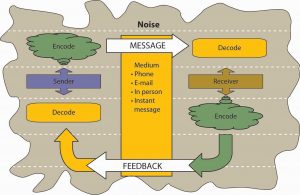

We all exchange information with others countless times a day, by phone, e-mail, printed word, and of course, in person. Let’s take a moment to see how a typical communication works using the Process Model of Communication as a guide.

The Process Model of Communication

A Sender, such as a boss, coworker, or customer, originates the Message with a thought. For example, the boss’s thought could be: “Get more printer toner cartridges!”

The boss may communicate this thought by saying, “Hey you guys, we need to order more printer toner cartridges.” The medium of this encoded Message may be spoken words, written words, or signs. The receiver is the person who receives the Message. The Receiver decodes the Message by assigning meaning to the words.

In this example, our Receiver, Bill, has a to-do list a mile long. “The boss must know how much work I already have.” the Receiver thinks. Bill’s mind translates his boss’s Message as, “Could you order some printer toner cartridges, in addition to everything else I asked you to do this week…if you can find the time?”

The meaning that the Receiver assigns may not be the meaning that the Sender intended because of such factors as noise. Noise is anything that interferes with or distorts the Message being transformed. Noise can be external in the environment (such as distractions) or it can be within the Receiver. For example, the Receiver may be highly nervous and unable to pay attention to the Message. Noise can even occur within the Sender: the Sender may be unwilling to take the time to convey an accurate Message or the words she chooses can be ambiguous and prone to misinterpretation.

Picture the next scene. The place: a staff meeting. The time: a few days later. The boss believes her Message has been received.

“Are the printer toner cartridges here yet?” she asks.

“You never said it was a rush job!” the Receiver protests.

“But!”

“But!”

Miscommunications like these happen in the workplace every day (Figure 6). We’ve seen that miscommunication does occur in the workplace. But how does a miscommunication happen? It helps to think of the communication process. The series of arrows pointing the way from the Sender to the Receiver and back again can, and often do, fall short of their target (Figure 7).

Key Takeaway

Communication is vital to organizations. Poor communication is prevalent and can have serious repercussions. Communication fulfills three functions within organizations: transmitting information, coordinating, and sharing emotions and feelings. Noise can disrupt or distort communication.

Barriers to Effective Communication

Communicating can be more of a challenge than you think, when you realize the many things that can stand in the way of effective communication. These include filtering, selective perception, information overload, emotional disconnects, lack of source familiarity or credibility, workplace gossip, semantics, gender differences, differences in meaning between Sender and Receiver, and biased language. Let’s examine each of these barriers.

Filtering

Filtering is the distortion or withholding of information to manage a person’s reactions. Some examples of filtering include a manager who keeps her division’s poor sales figures from her boss, the vice president, fearing that the bad news will make him angry. The old saying, “Don’t shoot the messenger!” illustrates the tendency of Receivers (in this case, the vice president) to vent their negative response to unwanted Messages on the Sender. A gatekeeper (the vice president’s assistant, perhaps) who doesn’t pass along a complete Message is also filtering. The vice president may delete the e-mail announcing the quarter’s sales figures before reading it, blocking the Message before it arrives.

As you can see, filtering prevents members of an organization from getting a complete picture of the way things are. To maximize your chances of sending and receiving effective communications, it’s helpful to deliver a Message in multiple ways and to seek information from multiple sources. In this way, the effect of any one person’s filtering the Message will be diminished.

Since people tend to filter bad news more during upward communication, it is also helpful to remember that those below you in an organization may be wary of sharing bad news. One way to defuse the tendency to filter is to reward employees who clearly convey information upward, regardless of whether the news is good and bad.

Selective perception refers to filtering what we see and hear to suit our own needs. This process is often unconscious. Small things can command our attention when we’re visiting a new place — a new city or a new company. Over time, however, we begin to make assumptions about the way things are on the basis of our past experience. Often, much of this process is unconscious. “We simply are bombarded with too much stimuli every day to pay equal attention to everything so we pick and choose according to our own needs (Pope, 2008).” Selective perception is a time-saver, a necessary tool in a complex culture. But it can also lead to mistakes.

Think back to the earlier example conversation between Bill, who was asked to order more toner cartridges, and his boss. Since Bill found his boss’s to-do list to be unreasonably demanding, he assumed the request could wait. (How else could he do everything else on the list?) The boss, assuming that Bill had heard the urgency in her request, assumed that Bill would place the order before returning to the other tasks on her list.

Both members of this organization were using selective perception to evaluate the communication. Bill’s perception was that the task of ordering could wait. The boss’s perception was that her time frame was clear, though unstated. When two selective perceptions collide, a misunderstanding occurs.

Information Overload

Information overload can be defined as “occurring when the information processing demands on an individual’s time to perform interactions and internal calculations exceed the supply or capacity of time available for such processing (Schick, et. al., 1990).” Messages reach us in countless ways every day. Some are societal — advertisements that we may hear or see in the course of our day. Others are professional — e-mails, and memos, voice mails, and conversations from our colleagues. Others are personal — messages and conversations from our loved ones and friends.

Add these together and it’s easy to see how we may be receiving more information than we can take in. This state of imbalance is known as information overload. Experts note that information overload is “A symptom of the high-tech age, which is too much information for one human being to absorb in an expanding world of people and technology. It comes from all sources including TV, newspapers, and magazines as well as wanted and unwanted regular mail, e-mail and faxes. It has been exacerbated enormously because of the formidable number of results obtained from Web search engines (PC Magazine, 2008).” Other research shows that working in such fragmented fashion has a significant negative effect on efficiency, creativity, and mental acuity (Overholt, 2001).

Going back to our example of Bill. Let’s say he’s in his cubicle on the phone with a supplier. While he’s talking, he hears the chime of e-mail alerting him to an important message from his boss. He’s scanning through it quickly, while still on the phone, when a coworker pokes his head around the cubicle corner to remind Bill that he’s late for a staff meeting. The supplier on the other end of the phone line has just given Bill a choice among the products and delivery dates he requested. Bill realizes he missed hearing the first two options, but he doesn’t have time to ask the supplier to repeat them all or to try reconnecting to place the order at a later time. He chooses the third option — at least he heard that one, he reasons, and it seemed fair. How good was Bill’s decision amid all the information he was processing at the same time?

Emotional disconnects

Emotional disconnects happen when the Sender or the Receiver is upset, whether about the subject at hand or about some unrelated incident that may have happened earlier. An effective communication requires a Sender and a Receiver who are open to speaking and listening to one another, despite possible differences in opinion or personality. One or both parties may have to put their emotions aside to achieve the goal of communicating clearly. A Receiver who is emotionally upset tends to ignore or distort what the Sender is saying. A Sender who is emotionally upset may be unable to present ideas or feelings effectively.

Lack of Source Credibility

Lack of source familiarity or credibility can derail communications, especially when humor is involved. Have you ever told a joke that fell flat? You and the Receiver lacked the common context that could have made it funny. (Or yes, it could have just been a lousy joke.) Sarcasm and irony are subtle, and potentially hurtful, commodities in business. It’s best to keep these types of communications out of the workplace as their benefits are limited, and their potential dangers are great. Lack of familiarity with the Sender can lead to misinterpreting humor, especially in less-rich information channels like e-mail. For example, an e-mail from Jill that ends with, “Men, like hens, should boil in vats of oil,” could be interpreted as antimale if the Receiver didn’t know that Jill has a penchant for rhyme and likes to entertain coworkers by making up amusing sayings.

Similarly, if the Sender lacks credibility or is untrustworthy, the Message will not get through. Receivers may be suspicious of the Sender’s motivations (“Why am I being told this?”). Likewise, if the Sender has communicated erroneous information in the past, or has created false emergencies, his current Message may be filtered.

Workplace gossip, also known as the grapevine, is a lifeline for many employees seeking information about their company (Kurland & Pelled, 2000). Researchers agree that the grapevine is an inevitable part of organizational life. Research finds that 70% of all organizational communication occurs at the grapevine level (Crampton, 1998).

Employees trust their peers as a source of Messages, but the grapevine’s informal structure can be a barrier to effective communication from the managerial point of view. Its grassroots structure gives it greater credibility in the minds of employees than information delivered through official channels, even when that information is false.

Some downsides of the office grapevine are that gossip offers politically minded insiders a powerful tool for disseminating communication (and self-promoting miscommunications) within an organization. In addition, the grapevine lacks a specific Sender, which can create a sense of distrust among employees — who is at the root of the gossip network? When the news is volatile, suspicions may arise as to the person or persons behind the Message. Managers who understand the grapevine’s power can use it to send and receive Messages of their own. They also decrease the grapevine’s power by sending official Messages quickly and accurately, should big news arise.

Semantics

Semantics is the study of meaning in communication. Words can mean different things to different people, or they might not mean anything to another person. For example, companies often have their own acronyms and buzzwords (called business jargon) that are clear to them but impenetrable to outsiders. For example, at IBM, GBS is focusing on BPTS, using expertise acquired from the PwC purchase (which had to be sold to avoid conflicts of interest in light of SOX) to fend other BPO providers and inroads by the Bangalore tiger. Does this make sense to you? If not, here’s the translation: IBM’s Global Business Services (GBS) division is focusing on offering companies Business Process Transformation Services (BPTS), using the expertise it acquired from purchasing the management consulting and technology services arm of PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC), which had to sell the division because of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX, enacted in response to the major accounting scandals like the Enron). The added management expertise puts it above business process outsourcing (BPO) vendors who focus more on automating processes rather than transforming and improving them. Chief among these BPO competitors is Wipro, often called the “Bangalore tiger” because of its geographic origin and aggressive growth.

Given the amount of Messages we send and receive every day, it makes sense that humans try to find shortcuts — a way to communicate things in code. In business, this code is known as jargon. Jargon is the language of specialized terms used by a group or profession. It is common shorthand among experts and if used sensibly can be a quick and efficient way of communicating. Most jargon consists of unfamiliar terms, abstract words, nonexistent words, acronyms, and abbreviations, with an occasional euphemism thrown in for good measure. Every profession, trade, and organization has its own specialized terms (Wright, 2008). At first glance, jargon seems like a good thing — a quicker way to send an effective communication, the way text message abbreviations can send common messages in a shorter, yet understandable way. But that’s not always how things happen. Jargon can be an obstacle to effective communication, causing listeners to tune out or fostering ill-feeling between partners in a conversation. When jargon rules the day, the Message can get obscured.

A key question to ask before using jargon is, “Who is the Receiver of my Message?” If you are a specialist speaking to another specialist in your area, jargon may be the best way to send a message while forging a professional bond — similar to the way best friends can communicate in code. For example, an information technology (IT) systems analyst communicating with another IT employee may use jargon as a way of sharing information in a way that reinforces the pair’s shared knowledge. But that same conversation should be held in standard English, free of jargon, when communicating with staff members outside the IT group.

Gender Differences

Gender differences in communication have been documented by a number of experts, including linguistics professor Deborah Tannen in her best-selling book You Just Don’t Understand: Women and Men in Conversation (Tannen, 1991). Men and women work together every day. But their different styles of communication can sometimes work against them. Generally speaking, women like to ask questions before starting a project, while men tend to “jump right in.” A male manager who’s unaware of how many women communicate their readiness to work may misperceive a ready employee as not ready.

Another difference that has been noticed is that men often speak in sports metaphors, while many women use their home as a starting place for analogies. Women who believe men are “only talking about the game” may be missing out on a chance to participate in a division’s strategy and opportunities for teamwork and “rallying the troops” for success (Krotz, 2008).

“It is important to promote the best possible communication between men and women in the workplace,” notes gender policy adviser Dee Norton, who provided the above example. “As we move between the male and female cultures, we sometimes have to change how we behave (speak the language of the other gender) to gain the best results from the situation. Clearly, successful organizations of the future are going to have leaders and team members who understand, respect and apply the rules of gender culture appropriately (Norton, 2008).”

Being aware of these gender differences can be the first step in learning to work with them, as opposed to around them. For example, keep in mind that men tend to focus more on competition, data, and orders in their communications, while women tend to focus more on cooperation, intuition, and requests. Both styles can be effective in the right situations, but understanding the differences is a first step in avoiding misunderstandings based on them.

Differences in meaning often exist between the Sender and Receiver. “Mean what you say, and say what you mean.” It’s an easy thing to say. But in business, what do those words mean? Different words mean different things to different people. Age, education, and cultural background are all factors that influence how a person interprets words. The less we consider our audience, the greater our chances of miscommunication will be. When communication occurs in the cross-cultural context, extra caution is needed given that different words will be interpreted differently across cultures and different cultures have different norms regarding nonverbal communication. Eliminating jargon is one way of ensuring that our words will convey real-world concepts to others. Speaking to our audience, as opposed to about ourselves, is another. Nonverbal Messages can also have different meanings.

Managers who speak about “long-term goals and profits” to a staff that has received scant raises may find their core Message (“You’re doing a great job — and that benefits the folks in charge!”) has infuriated the group they hoped to inspire. Instead, managers who recognize the “contributions” of their staff and confirm that this work is contributing to company goals in ways “that will benefit the source of our success — our employees as well as executives,” will find their core Message (“You’re doing a great job — we really value your work”) is received as opposed to being misinterpreted.

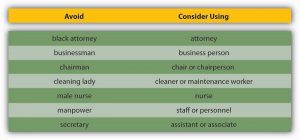

Avoiding Biased Language

Effective communication is clear, factual, and goal-oriented. It is also respectful. Referring to a person by one adjective (a brain, a diabetic, an invalid) reduces that person to that one characteristic. Language that belittles or stereotypes a person poisons the communication process. Language that insults an individual or group based on age, ethnicity, sexual preference, or political beliefs violates public and private standards of decency, ranging from civil rights to corporate regulations (Figure 8).

The effort to create a neutral set of terms to refer to heritage and preferences has resulted in a debate over the nature of “political correctness.” Proponents of political correctness see it as a way to defuse the volatile nature of words that stereotyped groups and individuals in the past. Critics of political correctness see its vocabulary as stilted and needlessly cautious.

Many companies offer new employees written guides on standards of speech and conduct. These guides, augmented by common sense and courtesy, are solid starting points for effective, respectful workplace communication. Tips for appropriate workplace speech include but are not limited to:

- Alternating the use of “he” and “she” when referring to people in general.

- Relying on human resources–generated guidelines.

- Remembering that terms that feel respectful or comfortable to us may not be comfortable or respectful to others.

Poor Listening and Active Listening

Former Chrysler CEO Lee Iacocca lamented, “I only wish I could find an institute that teaches people how to listen. After all, a good manager needs to listen at least as much as he needs to talk (Iacocca & Novak, 1984).” Research shows that listening skills are related to promotions (Sypher, et. al., 1989). A Sender may strive to deliver a Message clearly. But the Receiver’s ability to listen effectively is equally vital to effective communication. The average worker spends 55% of her workdays listening. Managers listen up to 70% each day. But listening doesn’t lead to understanding in every case. Listening takes practice, skill, and concentration.

According to University of San Diego professor Phillip Hunsaker, “The consequences of poor listening are lower employee productivity, missed sales, unhappy customers, and billions of dollars of increased cost and lost profits. Poor listening is a factor in low employee morale and increased turnover because employees do not feel their managers listen to their needs, suggestions, or complaints (Alessandra, et. al., 1993).” Clearly, if you hope to have a successful career in management, it behooves you to learn to be a good listener.

Alan Gulick, a Starbucks spokesperson, puts better listening to work in pursuit of better profits. If every Starbucks employee misheard one $10 order each day, he calculates, their errors would cost the company a billion dollars annually. To teach its employees to listen, Starbucks created a code that helps employees taking orders hear the size, flavor, and use of milk or decaf coffee. The person making the drink echoes the order aloud.

How can you improve your listening skills? The Roman philosopher Cicero said, “Silence is one of the great arts of conversation.” How often have we been in conversation with someone else where we are not really listening but itching to convey our portion? This behavior is known as “rehearsing.” It suggests the Receiver has no intention of considering the Sender’s Message and intends to respond to an earlier point instead. Clearly, rehearsing is an impediment to the communication process. Effective communication relies on another kind of listening: active listening.

Active listening can be defined as giving full attention to what other people are saying, taking time to understand the points being made, asking questions as appropriate, and not interrupting at inappropriate times (Onet Center, 2008).Active listening creates a real-time relationship between the Sender and the Receiver by acknowledging the content and receipt of a Message. As we’ve seen in the Starbucks example, repeating and confirming a Message’s content offers a way to confirm that the correct content is flowing between colleagues. The process creates a bond between coworkers while increasing the flow and accuracy of messaging.

Carl Rogers, founder of the “person-centered” approach to psychology, formulated five rules for active listening:

- Listen for message content

- Listen for feelings

- Respond to feelings

- Note all cues

- Paraphrase and restate

The good news is that listening is a skill that can be learned (Brownell, 1990). The first step is to decide that we want to listen. Casting aside distractions, such as by reducing background or internal noise, is critical. The Receiver takes in the Sender’s Message silently, without speaking. Second, throughout the conversation, show the speaker that you’re listening. You can do this nonverbally by nodding your head and keeping your attention focused on the speaker. You can also do it verbally, by saying things like, “Yes,” “That’s interesting,” or other such verbal cues. As you’re listening, pay attention to the Sender’s body language for additional cues about how they’re feeling. Interestingly, silence plays a major role in active listening. During active listening, we are trying to understand what has been said, and in silence, we can consider the implications. We can’t consider information and reply to it at the same time. That’s where the power of silence comes into play. Finally, if anything is not clear to you, ask questions. Confirm that you’ve heard the message accurately, by repeating back a crucial piece like, “Great, I’ll see you at 2 p.m. in my office.” At the end of the conversation, a “thank you” from both parties is an optional but highly effective way of acknowledging each other’s teamwork.

In summary, active listening creates a more dynamic relationship between a Receiver and a Sender. It strengthens personal investment in the information being shared. It also forges healthy working relationships among colleagues by making Speakers and Listeners equally valued members of the communication process.

Key Takeaway

Many barriers to effective communication exist. Examples include filtering, selective perception, information overload, emotional disconnects, lack of source familiarity or credibility, workplace gossip, semantics, gender differences, differences in meaning between Sender and Receiver, and biased language. The Receiver can enhance the probability of effective communication by engaging in active listening, which involves (1) giving one’s full attention to the Sender and (2) checking for understanding by repeating the essence of the Message back to the Sender.

Types of Communication

Communication can be categorized into three basic types: (1) verbal communication, in which you listen to a person to understand their meaning; (2) written communication, in which you read their meaning; and (3) nonverbal communication, in which you observe a person and infer meaning. Each has its own advantages, disadvantages, and even pitfalls.

Verbal Communication

Verbal communications in business take place over the phone or in person. The medium of the Message is oral. Let’s return to our printer cartridge example. This time, the Message is being conveyed from the Sender (the Manager) to the Receiver (an employee named Bill) by telephone. We’ve already seen how the Manager’s request to Bill (“We need to buy more printer toner cartridges”) can go awry. Now let’s look at how the same Message can travel successfully from Sender to Receiver.

Manager (speaking on the phone): “Good morning, Bill!”

(By using the employee’s name, the manager is establishing a clear, personal link to the Receiver.)

Manager: “Your division’s numbers are looking great.”

(The Manager’s recognition of Bill’s role in a winning team further personalizes and emotionalizes the conversation.)

Manager: “Our next step is to order more printer toner cartridges. Could you place an order for 1,000 printer toner cartridges with Jones Computer Supplies? Our budget for this purchase is $30,000, and the cartridges need to be here by Wednesday afternoon.”

(The Manager breaks down the task into several steps. Each step consists of a specific task, time frame, quantity, or goal.)

Bill: “Sure thing! I’ll call Jones Computer Supplies and order 1,000 more printer toner cartridges, not exceeding a total of $30,000, to be here by Wednesday afternoon.”

(Bill, who is good at active listening, repeats what he has heard. This is the Feedback portion of the communication, and verbal communication has the advantage of offering opportunities for immediate feedback. Feedback helps Bill to recognize any confusion he may have had hearing the manager’s Message. Feedback also helps the manager to tell whether she has communicated the Message correctly.)

Storytelling

Storytelling has been shown to be an effective form of verbal communication; it serves an important organizational function by helping to construct common meanings for individuals within the organization. Stories can help clarify key values and help demonstrate how things are done within an organization, and story frequency, strength, and tone are related to higher organizational commitment (McCarthy, 2008). The quality of the stories entrepreneurs tell is related to their ability to secure capital for their firms(Martens, et. al., 2007). Stories can serve to reinforce and perpetuate an organization’s culture, part of the organizing P-O-L-C function.

Crucial Conversations

While the process may be the same, high-stakes communications require more planning, reflection, and skill than normal day-to-day interactions at work. Examples of high-stakes communication events include asking for a raise or presenting a business plan to a venture capitalist. In addition to these events, there are also many times in our professional lives when we have crucial conversations — discussions where not only the stakes are high but also where opinions vary and emotions run strong (Patterson, et. al., 2002). One of the most consistent recommendations from communications experts is to work toward using “and” instead of “but” as you communicate under these circumstances. In addition, be aware of your communication style and practice flexibility; it is under stressful situations that communication styles can become the most rigid.

Written Communication

In contrast to verbal communications, written business communications are printed messages (Figure 9). Examples of written communications include memos, proposals, e-mails, letters, training manuals, and operating policies. They may be printed on paper, handwritten, or appear on the screen. Normally, a verbal communication takes place in real time. Written communication, by contrast, can be constructed over a longer period of time. Written communication is often asynchronous (occurring at different times). That is, the Sender can write a Message that the Receiver can read at any time, unlike a conversation that is carried on in real time. A written communication can also be read by many people (such as all employees in a department or all customers). It’s a “one-to-many” communication, as opposed to a one-to-one verbal conversation. There are exceptions, of course: a voicemail is an oral Message that is asynchronous. Conference calls and speeches are oral one-to-many communications, and e-mails may have only one recipient or many.

Most jobs involve some degree of writing. According to the National Commission on Writing, 67% of salaried employees in large American companies and professional state employees have some writing responsibility. Half of responding companies reported that they take writing into consideration when hiring professional employees, and 91% always take writing into account when hiring (for any position, not just professional-level ones) (Flink, 2007).

Luckily, it is possible to learn to write clearly. Here are some tips on writing well. Thomas Jefferson summed up the rules of writing well with this idea “Don’t use two words when one will do.” One of the oldest myths in business is that writing more will make us sound more important; in fact, the opposite is true. Leaders who can communicate simply and clearly project a stronger image than those who write a lot but say nothing.

Nonverbal Communication

What you say is a vital part of any communication. But what you don’t say can be even more important. Research also shows that 55% of in-person communication comes from nonverbal cues like facial expressions, body stance, and tone of voice. According to one study, only 7% of a Receiver’s comprehension of a Message is based on the Sender’s actual words; 38% is based on paralanguage (the tone, pace, and volume of speech), and 55% is based on nonverbal cues(body language) (Mehrabian, 1981).

Research shows that nonverbal cues can also affect whether you get a job offer. Judges examining videotapes of actual applicants were able to assess the social skills of job candidates with the sound turned off. They watched the rate of gesturing, time spent talking, and formality of dress to determine which candidates would be the most successful socially on the job (Gifford, et. al., 1985). For this reason, it is important to consider how we appear in business as well as what we say. The muscles of our faces convey our emotions. We can send a silent message without saying a word. A change in facial expression can change our emotional state. Before an interview, for example, if we focus on feeling confident, our face will convey that confidence to an interviewer. Adopting a smile (even if we’re feeling stressed) can reduce the body’s stress levels.

To be effective communicators, we need to align our body language, appearance, and tone with the words we’re trying to convey. Research shows that when individuals are lying, they are more likely to blink more frequently, shift their weight, and shrug (Siegman, 1985).

Listen Up and Learn More!

Another element of nonverbal communication is tone. A different tone can change the perceived meaning of a message demonstrates how clearly this can be true, whether in verbal or written communication. If we simply read these words without the added emphasis, we would be left to wonder, but the emphasis shows us how the tone conveys a great deal of information. Now you can see how changing one’s tone of voice or writing can incite or defuse a misunderstanding (Figure 10).

|

Don’t Use That Tone with Me! |

|

|

Placement of the emphasis |

What it means |

|

I did not tell John you were late. |

Someone else told John you were late. |

|

I did not tell John you were late. |

This did not happen. |

|

I did not tell John you were late. |

I may have implied it. |

|

I did not tell John you were late. |

But maybe I told Sharon and José. |

|

I did not tell John you were late. |

I was talking about someone else. |

|

I did not tell John you were late. |

I told him you still are late. |

|

I did not tell John you were late. |

I told him you were attending another meeting. |

Figure 10: Source: Based on ideas in Kiely, M. (1993, October). When “no” means “yes.” Marketing, 7–9.

For an example of the importance of nonverbal communication, imagine that you’re a customer interested in opening a new bank account. At one bank, the bank officer is dressed neatly. She looks you in the eye when she speaks. Her tone is friendly. Her words are easy to understand, yet she sounds professional. “Thank you for considering Bank of the East Coast. We appreciate this opportunity and would love to explore ways that we can work together to help your business grow,” she says with a friendly smile.

At the second bank, the bank officer’s tie is stained. He looks over your head and down at his desk as he speaks. He shifts in his seat and fidgets with his hands. His words say, “Thank you for considering Bank of the West Coast. We appreciate this opportunity and would love to explore ways that we can work together to help your business grow,” but he mumbles, and his voice conveys no enthusiasm or warmth.

To learn more about facial language from facial recognition expert Patrician McCarthy as she speaks with Senior Editor Suzanne Woolley at Business Week, view the online interview at http://feedroom.businessweek.com/index.jsp?fr_chl=1e2ee1e43e4a5402a862f79a7941fa625f5b0744.

Which bank would you choose?

The speaker’s body language must match his or her words. If a Sender’s words and body language don’t match — if a Sender smiles while telling a sad tale, for example — the mismatch between verbal and nonverbal cues can cause a Receiver to actively dislike the Sender.

Here are a few examples of nonverbal cues that can support or detract from a Sender’s Message.

- Body Language — A simple rule is that simplicity, directness, and warmth convey sincerity. And sincerity is key to effective communication. A firm handshake, given with a warm, dry hand, is a great way to establish trust. A weak, clammy handshake conveys a lack of trustworthiness. Gnawing one’s lip conveys uncertainty. A direct smile conveys confidence.

- Eye Contact — In business, the style and duration of eye contact considered appropriate vary greatly across cultures. In the United States, looking someone in the eye (for about a second) is considered a sign of trustworthiness.

- Facial Expressions — The human face can produce thousands of different expressions. These expressions have been decoded by experts as corresponding to hundreds of different emotional states (Ekman, et. al., 2008). Our faces convey basic information to the outside world. Happiness is associated with an upturned mouth and slightly closed eyes; fear with an open mouth and wide-eyed stare. Flitting (“shifty”) eyes and pursed lips convey a lack of trustworthiness. The effect of facial expressions in conversation is instantaneous. Our brains may register them as “a feeling” about someone’s character.

- Posture — The position of our body relative to a chair or another person is another powerful silent messenger that conveys interest, aloofness, professionalism — or lack thereof. Head up, back straight (but not rigid) implies an upright character. In interview situations, experts advise mirroring an interviewer’s tendency to lean in and settle back in her seat. The subtle repetition of the other person’s posture conveys that we are listening and responding.

- Touch — The meaning of a simple touch differs between individuals, genders, and cultures. In Mexico, when doing business, men may find themselves being grasped on the arm by another man. To pull away is seen as rude. In Indonesia, to touch anyone on the head or touch anything with one’s foot is considered highly offensive. In the Far East, according to business etiquette writer Nazir Daud, “it is considered impolite for a woman to shake a man’s hand” (Daud, 2008). Americans, as we have noted, place great value in a firm handshake. But handshaking as a competitive sport (“the bone-crusher”) can come off as needlessly aggressive, at home and abroad.

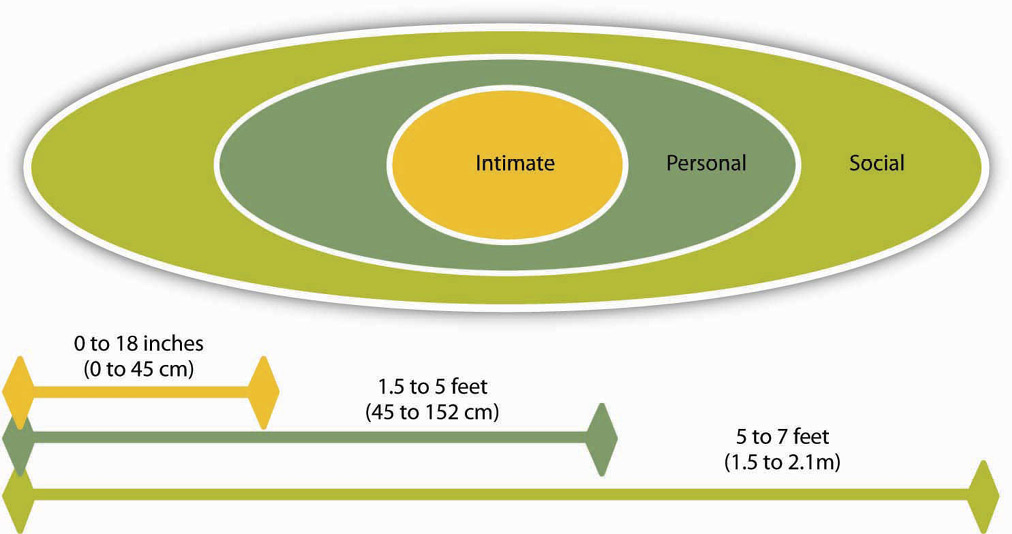

- Space — Anthropologist Edward T. Hall coined the term proxemics to denote the different kinds of distance that occur between people. These distances vary between cultures. The figure below outlines the basic proxemics of everyday life and their meaning (Hall, 1966) (Figure 11).

Key Takeaway

Types of communication include verbal, written, and nonverbal. Verbal communications have the advantage of immediate feedback, are best for conveying emotions, and can involve storytelling and crucial conversations. Written communications have the advantage of asynchronicity, of reaching many readers, and are best for conveying information. Both verbal and written communications convey nonverbal messages through tone; verbal communications are also colored by body language, eye contact, facial expression, posture, touch, and space.

By being sensitive to the errors outlined in this chapter and adopting active listening skills, you may increase your communication effectiveness, increasing your ability to carry out the managerial functions of planning, organizing, leading, and controlling. The following are additional tools for helping you increase your communication effectiveness.

Ten Ways to Improve Your Listening Habits

- Start by stopping. Take a moment to inhale and exhale quietly before you begin to listen. Your job as a listener is to receive information openly and accurately.

- Don’t worry about what you’ll say when the time comes. Silence can be a beautiful thing.

- Join the Sender’s team. When she pauses, summarize what you believe she has said. “What I’m hearing is that we need to focus on marketing as well as sales. Is that correct?” Be attentive to physical as well as verbal communications. “I hear you saying that we should focus on marketing. But the way you’re shaking your head tells me the idea may not really appeal to you — is that right?”

- Don’t multitask while listening. Listening is a full-time job. It’s tempting to multitask when you and the Sender are in different places, but doing that is counterproductive. The human mind can only focus on one thing at a time. Listening with only half your brain increases the chances that you’ll have questions later, requiring more of the Speaker’s time. (And when the speaker is in the same room, multitasking signals a disinterest that is considered rude.)

- Try to empathize with the Sender’s point of view. You don’t have to agree; but can you find common ground?

- Confused? Ask questions. There’s nothing wrong with admitting you haven’t understood the Sender’s point. You may even help the Sender clarify the Message.

- Establish eye contact. Making eye contact with the speaker (if appropriate for the culture) is important.

- What is the goal of this communication? Ask yourself this question at different points during the communication to keep the information flow on track. Be polite. Differences in opinion can be the starting point of consensus.

- It’s great to be surprised. Listen with an open mind, not just for what you want to hear.

- Pay attention to what is not said. Does the Sender’s body language seem to contradict her Message? If so, clarification may be in order.

Career-Friendly Communications

Communication can occur without your even realizing it. Consider the following: Is your e-mail name professional? The typical convention for business e-mail contains some form of your name. While an e-mail name like “LazyGirl” or “DeathMonkey” may be fine for chatting online with your friends, they may send the wrong signal to individuals you e-mail such as professors and prospective employers.

- Is your outgoing voice mail greeting professional? If not, change it. Faculty and prospective recruiters will draw certain conclusions if, upon calling you, they hear a message that screams, “Party, party, party!”

- Do you have a “private” social networking Web site on MySpace.com, Facebook.com, or Xanga.com? If so, consider what it says about you to employers or clients. If it is information you wouldn’t share at work, it probably shouldn’t be there.

- Googled yourself lately? If not, you probably should. Potential employers have begun searching the Web as part of background checking and you should be aware of what’s out there about you.

Communication Freezers

Communication freezers put an end to effective communication by making the Receiver feel judged or defensive. Typical communication stoppers include criticizing, blaming, ordering, judging, or shaming the other person. The following are some examples of things to avoid saying (Tramel & Reynolds, 1981; Saltman & O’Dea, 2008):

- Telling people what to do:

- “You must…”

- “You cannot…”

- Threatening with “or else” implied:

- “You had better…”

- “If you don’t…”

- Making suggestions or telling other people what they ought to do:

- “You should…”

- “It’s your responsibility to…”

- Attempting to educate the other person:

- “Let me give you the facts.”

- “Experience tells us that…”

- Judging the other person negatively:

- “You’re not thinking straight.”

- “You’re wrong.”

- Giving insincere praise:

- “You have so much potential.”

- “I know you can do better than this.”

- Psychoanalyzing the other person:

- “You’re jealous.”

- “You have problems with authority.”

- Making light of the other person’s problems by generalizing:

- “Things will get better.”

- “Behind every cloud is a silver lining.”

- Asking excessive or inappropriate questions:

- “Why did you do that?”

- “Who has influenced you?”

- Making light of the problem by kidding:

- “Think about the positive side.”

- “You think you’ve got problems!”

Key Takeaway

By practicing the skills associated with active listening, you can become more effective in your personal and professional relationships. Managing your online communications appropriately can also help you avoid career pitfalls. Finally, be aware of the types of remarks that freeze communication and try not to use them.

References – Communication section

Alsop, R. (2006, September 20). The top business schools: Recruiters’ M.B.A. picks. Wall Street Journal Online. Retrieved September 20, 2006 from http://online.wsj.com/article/SB115860376846766495.html?mod=2_1245_1.

Armour, S. (1998, September 30). Failure to Communicate Costly for Companies. USA Today, 1A.

Baron, R. (2004). Barriers to effective communication: Implications for the cockpit. Retrieved July 3, 2008, from AirlineSafety.com: http://www.airlinesafety.com/editorials/BarriersToCommunication.htm.

Meisinger, S. (2003, February). Enhancing communications — ours and yours. HR Magazine. Retrieved July 1, 2008, from http://www.shrm.org/hrmagazine/archive/0203toc.asp.

Mercer, What are the bottom line results of communicating? (2003, June). Pay for Performance Report, p. 1. Retrieved July 1, 2008, from http://www.mercerHR.com.

Merriam-Webster online dictionary. (2008). Retrieved December 1, 2008, from http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/communication.

Penley, L. E., Alexander, E. R., Jernigan, I. E., & Henwood, C. I. (1991). Communication abilities of managers: The relationship of performance. Journal of Management, 17, 57–76.

Schnake, M. E., Dumler, M. P., Cochran, D. S., & Barnett, T. R. (1990). Effects of differences in subordinate perceptions of superiors’ communication practices. The Journal of Business Communication, 27, 37–50.

References-Barriers to Effective Communication

Alessandra, T. (1993). Communicating at work. New York: Fireside.

Alessandra, T., Garner, H., & Hunsaker, P. L. (1993). Communicating at work. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Ashcraft, K., & Mumby, D. K. (2003). Reworking gender. Thousand Oaks, CA, Sage; Miller, C., &.

Brownell, J. (1990). Perceptions of effective listeners: A management study. Journal of Business Communications, 27, 401–415.

Crampton, S. M. (1998). The informal communication network: factors influencing grapevine activity.

Public Personnel Management. Retrieved July 2, 2008, from http://www.allbusiness.com/management/735210-1.html.

Iacocca, L., & Novak, W. (1984). Iacocca: An autobiography. New York: Bantam Press.

Krotz, J. L. (n.d.). 6 tips for bridging the communication gap. Retrieved July 2, 2008, from Microsoft Small Business Center Web site, http://www.microsoft.com/smallbusiness/resources/management/leadership-training/women-vs-men-6-tips-for-bridging-the-communication-gap.aspx.

Kurland, N. B., & Pelled, L. H. (2000). Passing the word: Toward a model of gossip and power in the workplace. Academy of Management Review, 25, 428–438.

Norton, D. Gender and communication — finding common ground. Retrieved July 2, 2008, from http://www.uscg.mil/leadership/gender.htm.

O*NET Resource Center, the nation’s primary source of occupational information. Retrieved July 2, 2008, from http://online.onetcenter.org/skills.

Overholt, A. (2001, February). Intel’s got (too much) mail. Fast Company. Retrieved July 2, 2008, from http://www.fastcompany.com/online/44/intel.html and http://blogs.intel.com/it/2006/10/information_overload.php.

PC Magazine, retrieved July 1, 2008, from PC Magazine encyclopedia Web site, http://www.pcmag.com/encyclopedia_term/0,2542,t=information+overload&i=44950,00.asp, and reinforced by information in Dawley, D. D., & Anthony, W. P. (2003). User perceptions of e-mail at work.

Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 17, 170–200.

Pope, R. R. Selective perception. Illinois State University. Retrieved December 1, 2008, from http://lilt.ilstu.edu/rrpope/rrpopepwd/articles/perception3.html.

Schick, A. G., Gordon, L. A., & Haka, S. (1990). Information overload: A temporal approach. Accounting, Organizations, and Society, 15, 199–220.

Swift, K. (1980). The handbook of nonsexist writing. New York: Lippincott & Crowell; Procter, M. (2007, September 11). Unbiased language. Retrieved July 2, 2008, from http://www.utoronto.ca/writing/unbias.html.

Sypher, B. D., Bostrom, R. N., & Seibert, J. H. (1989). Listening, communication abilities, and success at work. Journal of Business Communication, 26, 293–303.

Tannen, D. (1991). You just don’t understand: Women and men in conversation. New York: Ballantine.

Wright, N. Keep it jargon-free. Retrieved July 2, 2008, from http://www.plainlanguage.gov/howto/wordsuggestions/jargonfree.cfm.

References – Types of Communication

Daud, N. (n.d.). Business etiquette. Retrieved July 2, 2008, from http://ezinearticles.com/?Business-Etiquette — Shaking-Hands-around-the-World&id=746227.

Ekman, P., Friesen, W. V., & Hager, J. C. The facial action coding system (FACS). Retrieved July 2, 2008, from http://face-and-emotion.com/dataface/facs/manual.

Flink, H. (2007, March). Tell it like it is: Essential communication skills for engineers. Industrial Engineer, 39, 44–49.

Gifford, R., Ng, C. F., & Wilkinson, M. (1985). Nonverbal cues in the employment interview: Links between applicant qualities and interviewer judgments. Journal of Applied Psychology, 70, 729–736.

Hall, E. T. (1966). The hidden dimension. New York: Doubleday.

Martens, M. L., Jennings, J. E., & Devereaux, J. P. (2007). Do the stories they tell get them the money they need? The role of entrepreneurial narratives in resource acquisition. Academy of Management Journal, 50, 1107–1132.

McCarthy, J. F. (2008). Short stories at work: Storytelling as an indicator of organizational commitment. Group & Organization Management, 33, 163–193.

Mehrabian, A. (1981). Silent messages. New York: Wadsworth.

Patterson, K., Grenny, J., McMillan, R., & Switzler, A. (2002). Crucial conversations: Tools for talking when stakes are high. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Siegman, A. W. (1985). Multichannel integrations of nonverbal behavior. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

References – Developing Communication Skill

Saltman, D., & O’Dea, N. (n.d.). Conflict management workshop powerpoint presentation. Retrieved July 1, 2008, from http://www.nswrdn.com.au/client_images/6806.PDF; Communication stoppers. Retrieved July 1, 2008, from Mental Health TodayWeb site: http://www.mental-health-today.com/Healing/communicationstop.htm.

Tramel, M., & Reynolds, H. (1981). Executive leadership. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.