1

Essential Questions

- Who were they key figures in the development of what we know today as I/O Psychology?

- How has the world of work changed since the late 19th century?

- What current factors and trends are impacting work in the 21st century?

- What are the component disciplines of I/O Psychology?

- Where do I/O psychologists work, and what do they do?

The Historical Development Of Industrial And Organizational Psychology

Industrial and organizational psychology had its origins in the early 20th century. Several influential early psychologists studied issues that today would be categorized as industrial psychology: James Cattell (1860–1944) at Columbia, Hugo Münsterberg (1863–1916) at Harvard, Walter Dill Scott (1869–1955) at Northwestern, Robert Yerkes (1876–1956) and Walter Bingham (1880–1952) at Dartmouth, and Lillian Gilbreth (1878–1972) at Purdue. Cattell, Münsterberg, and Scott had been students of Wilhelm Wundt, the father of experimental psychology. Some of these researchers had been involved in work in the area of industrial psychology before World War I. Cattell’s contribution to industrial psychology is largely reflected in his founding of a psychological consulting company, which is still operating today called the Psychological Corporation, and in the accomplishments of students at Columbia in the area of industrial psychology. In 1913, Münsterberg published Psychology and Industrial Efficiency, which covered topics such as employee selection, employee training, and effective advertising.

Scott was one of the first psychologists to apply psychology to advertising, management, and personnel selection. In 1903, Scott published two books: The Theory of Advertising and Psychology of Advertising. They are the first books to describe the use of psychology in the business world. By 1911 he published two more books, Influencing Men in Business and Increasing Human Efficiency in Business. In 1916 a newly formed division in the Carnegie Institute of Technology hired Scott to conduct applied research on employee selection (Katzell & Austin, 1992).

The focus of all this research was in what we now know as industrial psychology; it was only later in the century that the field of organizational psychology developed as an experimental science (Katzell & Austin, 1992). In addition to their academic positions, these researchers also worked directly for businesses as consultants.

The involvement of the United States in World War I in April 1917 catalyzed the participation in the military effort of psychologists working in this area. Yerkes organized a group under the Surgeon General’s Office (SGO) that developed methods for screening and selecting enlisted men. They developed the Army Alpha test to measure mental abilities. The Army Beta test was a non-verbal form of the test that was administered to illiterate and non-English-speaking draftees. Scott and Bingham organized a group under the Adjutant General’s Office (AGO) with the goal to develop selection methods for officers. They created a catalogue of occupational needs for the Army, essentially a job-description system and a system of performance ratings and occupational skill tests for officers (Katzell & Austin, 1992).

After the war, work on personnel selection continued. For example, Millicent Pond, who received a PhD from Yale University, worked at several businesses and was director of employment test research at Scoville Manufacturing Company. She researched the selection of factory workers, comparing the results of pre-employment tests with various indicators of job performance. These studies were published in a series of research articles in the Journal of Personnel Research in the late 1920s (Vinchur & Koppes, 2014).

From 1929 to 1932 Elton Mayo (1880–1949) and his colleagues began a series of studies at a plant near Chicago, Western Electric’s Hawthorne Works (Figure 1). This long-term project took industrial psychology beyond just employee selection and placement to a study of more complex problems of interpersonal relations, motivation, and organizational dynamics. These studies mark the origin of organizational psychology. They began as research into the effects of the physical work environment (e.g., level of lighting in a factory), but the researchers found that the psychological and social factors in the factory were of more interest than the physical factors. These studies also examined how human interaction factors, such as supervisorial style, enhanced or decreased productivity.

Analysis of the findings by later researchers led to the term the Hawthorne effect, which describes the increase in performance of individuals who are noticed, watched, and paid attention to by researchers or supervisors (Figure 2). What the original researchers found was that any change in a variable, such as lighting levels, led to an improvement in productivity; this was true even when the change was negative, such as a return to poor lighting. The effect faded when the attention faded (Roethlisberg & Dickson, 1939). The Hawthorne-effect concept endures today as an important experimental consideration in many fields and a factor that has to be controlled for in an experiment. In other words, an experimental treatment of some kind may produce an effect simply because it involves greater attention of the researchers on the participants (McCarney et al., 2007).

Watch the video at http://openstaxcollege.org/l/ATT to hear first-hand accounts of the original Hawthorne studies from those who participated in the research.

In the 1930s, researchers began to study employees’ feelings about their jobs. Kurt Lewin also conducted research on the effects of various leadership styles, team structure, and team dynamics (Katzell & Austin, 1992). Lewin is considered the founder of social psychology and much of his work and that of his students produced results that had important influences in organizational psychology. Lewin and his students’ research included an important early study that used children to study the effect of leadership style on aggression, group dynamics, and satisfaction (Lewin, Lippitt, & White, 1939). Lewin was also responsible for coining the term group dynamics, and he was involved in studies of group interactions, cooperation, competition, and communication that bear on organizational psychology.

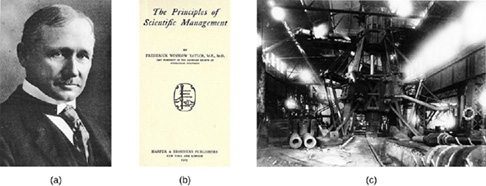

Parallel to these studies in industrial and organizational psychology, the field of human factors psychology was also developing. Frederick Taylor was an engineer who saw that if one could redesign the workplace there would be an increase in both output for the company and wages for the workers. In 1911 he put forward his theory in a book titled, The Principles of Scientific Management (Figure 3). His book examines management styles, personnel selection and training, as well as the work itself, using time and motion studies.

One of the examples of Taylor’s theory in action involved workers handling heavy iron ingots. Taylor showed that the workers could be more productive by taking work rests. This method of rest increased worker productivity from 12.5 to 47.0 tons moved per day with less reported fatigue as well as increased wages for the workers who were paid by the ton. At the same time, the company’s cost was reduced from 9.2 cents to 3.9 cents per ton. Despite these increases in productivity, Taylor’s theory received a great deal of criticism at the time because it was believed that it would exploit workers and reduce the number of workers needed. Also controversial was the underlying concept that only a manager could determine the most efficient method of working, and that while at work, a worker was incapable of this. Taylor’s theory was underpinned by the notion that a worker was fundamentally lazy and the goal of Taylor’s scientific management approach was to maximize productivity without much concern for worker well-being. His approach was criticized by unions and those sympathetic to workers (Van De Water, 1997).

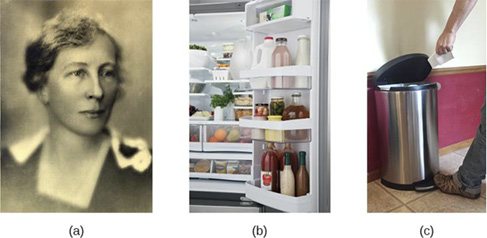

Gilbreth was another influential I-O psychologist who strove to find ways to increase productivity (Figure 4). Using time and motion studies, Gilbreth and her husband, Frank, worked to make workers more efficient by reducing the number of motions required to perform a task. She not only applied these methods to industry but also to the home, office, shops, and other areas. She investigated employee fatigue and time management stress and found many employees were motivated by money and job satisfaction. In 1914, Gilbreth wrote the book title, The Psychology of Management: The Function of the Mind in Determining, Teaching, and Installing Methods of Least Waste, and she is known as the mother of modern management. Some of Gilbreth’s contributions are still in use today: you can thank her for the idea to put shelves inside on refrigerator doors, and she also came up with the concept of using a foot pedal to operate the lid of trash can (Gilbreth, 1914, 1998; Koppes, 1997; Lancaster, 2004). Gilbreth was the first woman to join the American Society of Mechanical Engineers in 1926, and in 1966 she was awarded the Hoover Medal of the American Society of Civil Engineers.

Taylor and Gilbreth’s work improved productivity, but these innovations also improved the fit between technology and the human using it. The study of machine–human fit is known as ergonomics or human factors psychology.

World War II also drove the expansion of industrial psychology. Bingham was hired as the chief psychologist for the War Department (now the Department of Defense) and developed new systems for job selection, classification, training, ad performance review, plus methods for team development, morale change, and attitude change (Katzell & Austin, 1992). Other countries, such as Canada and the United Kingdom, likewise saw growth in I-O psychology during World War II (McMillan, Stevens, & Kelloway, 2009). In the years after the war, both industrial psychology and organizational psychology became areas of significant research effort. Concerns about the fairness of employment tests arose, and the ethnic and gender biases in various tests were evaluated with mixed results. In addition, a great deal of research went into studying job satisfaction and employee motivation (Katzell & Austin, 1992).

The Changing Nature of Work

The American Dream has always been based on opportunity. There is a great deal of mythologizing about the energetic upstart who can climb to success based on hard work alone. Common wisdom states that if you study hard, develop good work habits, and graduate high school or, even better, college, then you’ll have the opportunity to land a good job. That has long been seen as the key to a successful life.

Polarization in the Workforce

The mix of jobs available in the United States began changing many years before the 2008 recession struck, and, as mentioned above, the American Dream has not always been easy to achieve. Geography, race, gender, and other factors have always played a role in the reality of success. More recently, the increased outsourcing — or contracting a job or set of jobs to an outside source — of manufacturing jobs to developing nations has greatly diminished the number of high-paying, often unionized, blue-collar positions available. A similar problem has arisen in the white-collar sector, with many low-level clerical and support positions also being outsourced, as evidenced by the international technical-support call centers in Mumbai, India, and Newfoundland, Canada. The number of supervisory and managerial positions has been reduced as companies streamline their command structures and industries continue to consolidate through mergers. Even highly educated skilled workers such as computer programmers have seen their jobs vanish overseas.

The automation of the workplace, which replaces workers with technology, is another cause of the changes in the job market. Computers can be programmed to do many routine tasks faster and less expensively than people who used to do such tasks. Jobs like bookkeeping, clerical work, and repetitive tasks on production assembly lines all lend themselves to automation. Envision your local supermarket’s self-scan checkout aisles. The automated cashiers affixed to the units take the place of paid employees. Now one cashier can oversee transactions at six or more self-scan aisles, which was a job that used to require one cashier per aisle.

Despite the ongoing economic recovery, the job market is actually growing in some areas, but in a very polarized fashion. Polarization means that a gap has developed in the job market, with most employment opportunities at the lowest and highest levels and few jobs for those with midlevel skills and education. At one end, there has been strong demand for low-skilled, low-paying jobs in industries like food service and retail. On the other end, some research shows that in certain fields there has been a steadily increasing demand for highly skilled and educated professionals, technologists, and managers. These high-skilled positions also tend to be highly paid (Autor 2010).

The fact that some positions are highly paid while others are not is an example of the class system, an economic hierarchy in which movement (both upward and downward) between various rungs of the socioeconomic ladder is possible. Theoretically, at least, the class system as it is organized in the United States is an example of a meritocracy, an economic system that rewards merit — typically in the form of skill and hard work — with upward mobility. A theorist working in the functionalist perspective might point out that this system is designed to reward hard work, which encourages people to strive for excellence in pursuit of reward. A theorist working in the conflict perspective might counter with the thought that hard work does not guarantee success even in a meritocracy, because social capital — the accumulation of a network of social relationships and knowledge that will provide a platform from which to achieve financial success — in the form of connections or higher education are often required to access the high-paying jobs. Increasingly, we are realizing intelligence and hard work aren’t enough. If you lack knowledge of how to leverage the right names, connections, and players, you are unlikely to experience upward mobility.

Changing Job Demand

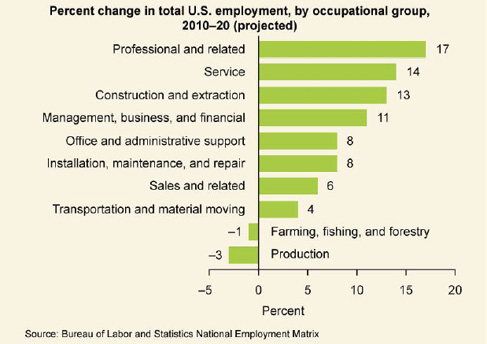

With so many jobs being outsourced or eliminated by automation, what kind of jobs are there a demand for in the United States? While fishing and forestry jobs are in decline, in several markets jobs are increasing. These include community and social service, personal care and service, finance, computer and information services, and healthcare. The chart below, from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, illustrates areas of projected growth.

The professional and related jobs, which include any number of positions, typically require significant education and training and tend to be lucrative career choices. Service jobs, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, can include everything from jobs with the fire department to jobs scooping ice cream (Bureau of Labor Statistics 2010). There is a wide variety of training needed, and therefore an equally large wage potential discrepancy. One of the largest areas of growth by industry, rather than by occupational group (as seen above), is in the health field. This growth is across occupations, from associate-level nurse’s aides to management-level assisted-living staff. As baby boomers age, they are living longer than any generation before, and the growth of this population segment requires an increase in capacity throughout our country’s elder care system, from home healthcare nursing to geriatric nutrition.

Notably, jobs in farming are in decline. This is an area where those with less education traditionally could be assured of finding steady, if low-wage, work. With these jobs disappearing, more and more workers will find themselves untrained for the types of employment that are available (Figure 5).

More Training Required

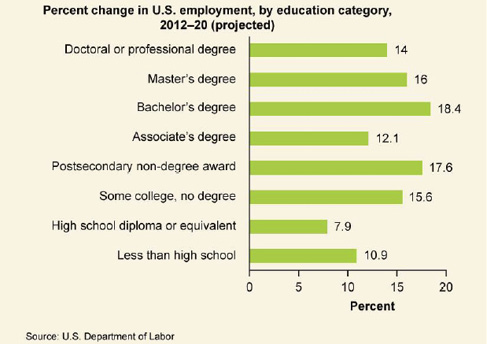

Another projected trend in employment relates to the level of education and training required to gain and keep a job. As the chart below shows us, growth rates are higher for those with more education. Those with a professional degree or a master’s degree may expect job growth of 20 and 22 percent respectively, and jobs that require a bachelor’s degree are projected to grow 17 percent. At the other end of the spectrum, jobs that require a high school diploma or equivalent are projected to grow at only 12 percent, while jobs that require less than a high school diploma will grow 14 percent. Quite simply, without a degree, it will be more difficult to find a job. It is worth noting that these projections are based on overall growth across all occupation categories, so obviously there will be variations within different occupational areas. However, once again, those who are the least educated will be the ones least able to fulfill the American Dream.

In the past, rising education levels in the United States had been able to keep pace with the rise in the number of education-dependent jobs. However, since the late 1970s, men have been enrolling in college at a lower rate than women, and graduating at a rate of almost 10 percent less. The lack of male candidates reaching the education levels needed for skilled positions has opened opportunities for women, minorities, and immigrants (Wang 2011) (Figure 6).

Women in the Workforce

Women have been entering the workforce in ever-increasing numbers for several decades. They have also been finishing college and going on to earn higher degrees at higher rate than men do. This has resulted in many women being better positioned to obtain high-paying, high-skill jobs (Autor 2010). While women are getting more and better jobs and their wages are rising more quickly than men’s wages are, U.S. Census statistics show that they are still earning only 77 percent of what men are for the same positions (U.S. Census Bureau 2010).

Immigration and the Workforce

Simply put, people will move from where there are few or no jobs to places where there are jobs, unless something prevents them from doing so. The process of moving to a country is called immigration. Due to its reputation as the land of opportunity, the United States has long been the destination of all skill levels of workers. While the rate decreased somewhat during the economic slowdown of 2008, immigrants, both legal and illegal, continue to be a major part of the U.S. workforce.

In 2005, before the recession arrived, immigrants made up a historic high of 14.7 percent of the workforce (Lowell et al. 2006). During the 1970s through 2000s, the United States experienced both an increase in college-educated immigrants and in immigrants who lacked a high school diploma. With this range across the spectrum, immigrants are well positioned for both the higher-paid jobs and the low-wage low-skill jobs that are predicted to grow in the next decade (Lowell et al. 2006). In the early 2000s, it certainly seemed that the United States was continuing to live up to its reputation of opportunity. But what about during the recession of 2008, when so many jobs were lost and unemployment hovered close to 10 percent? How did immigrant workers fare then?

The answer is that as of June 2009, when the National Bureau of Economic Research (NEBR) declared the recession officially over, “foreign-born workers gained 656,000 jobs while native-born workers lost 1.2 million jobs” (Kochhar 2010). As these numbers suggest, the unemployment rate that year decreased for immigrant workers and increased for native workers. The reasons for this trend are not entirely clear. Some Pew research suggests immigrants tend to have greater flexibility to move from job to job and that the immigrant population may have been early victims of the recession, and thus were quicker to rebound (Kochhar 2010). Regardless of the reasons, the 2009 job gains are far from enough to keep them inured from the country’s economic woes. Immigrant earnings are in decline, even as the number of jobs increases, and some theorize that increase in employment may come from a willingness to accept significantly lower wages and benefits.

While the political debate is often fueled by conversations about low-wage-earning immigrants, there are actually as many highly skilled — and high-earning — immigrant workers as well. Many immigrants are sponsored by their employers who claim they possess talents, education, and training that are in short supply in the U.S. These sponsored immigrants account for 15 percent of all legal immigrants (Batalova and Terrazas 2010). Interestingly, the U.S. population generally supports these high-level workers, believing they will help lead to economic growth and not be a drain on government services (Hainmueller and Hiscox 2010). On the other hand, illegal immigrants tend to be trapped in extremely low-paying jobs in agriculture, service, and construction with few ways to improve their situation without risking exposure and deportation.

I/O Psychology Today

Industrial and organizational psychologists work in four main contexts: academia, government, consulting firms, and business. Most I-O psychologists have a master’s or doctorate degree. The field of I-O psychology can be divided into three broad areas: industrial, organizational, and human factors. Industrial psychology is concerned with describing job requirements and assessing individuals for their ability to meet those requirements. In addition, once employees are hired, industrial psychology studies and develops ways to train, evaluate, and respond to those evaluations. As a consequence of its concern for candidate characteristics, industrial psychology must also consider issues of legality regarding discrimination in hiring.

Organizational psychology is a discipline interested in how the relationships among employees affect those employees and the performance of a business. This includes studying worker satisfaction, motivation, and commitment. This field also studies management, leadership, and organizational culture, as well as how an organization’s structures, management and leadership styles, social norms, and role expectations affect individual behavior. As a result of its interest in worker well-being and relationships, organizational psychology also considers the subjects of harassment, including sexual harassment, and workplace violence.

Human factors psychology is the study of how workers interact with the tools of work and how to design those tools to optimize workers’ productivity, safety, and health. These studies can involve interactions as straightforward as the fit of a desk, chair, and computer to a human having to sit on the chair at the desk using the computer for several hours each day. They can also include the examination of how humans interact with complex displays and their ability to interpret them accurately and quickly. In Europe, this field is referred to as ergonomics (Figure 7).

I/O Psychologists in the Modern Era

The U.S. Department of Labor estimates that I/O psychology, as a field, will grow 26% by the year 2018. I/O psychologists typically have advanced degrees such as a Ph.D. or master’s degree and may work in academic, consulting, government, military, or private for-profit and not-for-profit organizational settings. Depending on the state in which they work, I/O psychologists may be licensed. They might ask and answer questions such as “What makes people happy at work?” “What motivates employees at work?” “What types of leadership styles result in better performance of employees?” “Who are the best applicants to hire for a job?” One hallmark of I/O psychology is its basis in data and evidence to answer such questions, and I/O psychology is based on the scientist-practitioner model.

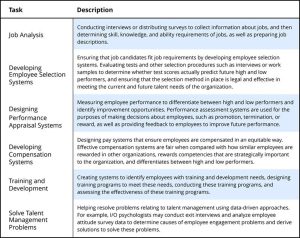

The table (Figure 8) presents a list of tasks I/O psychologists may perform in their work. This is an extensive list, and one person will not be responsible for all these tasks. The I/O psychology field prepares and trains individuals to be more effective in performing the tasks listed in this table.

At this point you may be asking yourself: Does psychology really need a special field to study work behaviors? In other words, wouldn’t the findings of general psychology be sufficient to understand how individuals behave at work? The answer is an underlined no. Employees behave differently at work compared with how they behave in general. While some fundamental principles of psychology definitely explain how employees behave at work (such as selective perception or the desire to relate to those who are similar to us), organizational settings are unique. To begin with, organizations have a hierarchy. They have job descriptions for employees. Individuals go to work not only to seek fulfillment and to remain active, but also to receive a paycheck and satisfy their financial needs. Even when they dislike their jobs, many stay and continue to work until a better alternative comes along.

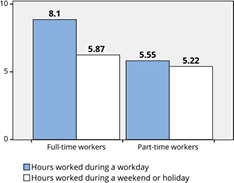

All these constraints suggest that how we behave at work may be somewhat different from how we would behave without these constraints. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, in 2011, more than 149 million individuals worked at least part time and spent many hours of the week working — see (Figure 9) for a breakdown (U.S. Department of Labor, 2011). In other words, we spend a large portion of our waking hours at work. How happy we are with our jobs and our careers is a primary predictor of how happy and content we are with our lives in general (Erdogan, Bauer, Truxillo, & Mansfield, 2012). Therefore, the I/O psychology field has much to offer to individuals and organizations interested in increasing employee productivity, retention, and effectiveness while at the same time ensuring that employees are happy and healthy.

It seems that I/O psychology is useful for organizations, but how is it helpful to you? Findings of I/O psychology are useful and relevant to everyone who is planning to work in an organizational setting. Note that we are not necessarily talking about a business setting. Even if you are planning to form your own band, or write a novel, or work in a not-for-profit organization, you will likely be working in, or interacting with, organizations. Understanding why people behave the way they do will be useful to you by helping you motivate and influence your coworkers and managers, communicate your message more effectively, negotiate a contract, and manage your own work life and career in a way that fits your life and career goals.

Careers in I/O Psychology

The U.S. Department of Labor estimates that I/O psychology as a field is expected to grow 26% by the year 2018 (American Psychological Association, 2011) so the job outlook for I/O psychologists is good. Helping organizations understand and manage their workforce more effectively using science-based tools is important regardless of the shape of the economy, and I/O psychology as a field remains a desirable career option for those who have an interest in psychology in a work-related context coupled with an affinity for research methods and statistics (Figure 10).

If you would like to refer to yourself as a psychologist in the United States, then you would need to be licensed, and this requirement also applies to I/O psychologists. Licensing requirements vary by state (see www.siop.org for details). However, it is possible to pursue a career relating to I/O psychology without holding the title psychologist. Licensing requirements usually include a doctoral degree in psychology. That said, there are many job opportunities for those with a master’s degree in I/O psychology, or in related fields such as organizational behavior and human resource management.

Academics and practitioners who work in I/O psychology or related fields are often members of the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology (SIOP). Students with an interest in I/O psychology are eligible to become an affiliated member of this organization, even if they are not pursuing a degree related to I/O psychology. SIOP membership brings benefits including networking opportunities and subscriptions to an academic journal of I/O research and a newsletter detailing current issues in I/O. The organization supports its members by providing forums for information and idea exchange, as well as monitoring developments about the field for its membership. SIOP is an independent organization but also a subdivision of American Psychological Association (APA), which is the scientific organization that represents psychologists in the United States. Different regions of the world have their own associations for I/O psychologists. For example, the European Association for Work and Organizational Psychology (EAWOP) is the premiere organization for I/O psychologists in Europe, where I/O psychology is typically referred to as work and organizational psychology. A global federation of I/O psychology organizations, named the Alliance for Organizational Psychology, was recently established. It currently has three member organizations (SIOP, EAWOP, and the Organizational Psychology Division of the International Association for Applied Psychology, or Division 1), with plans to expand in the future. The Association for Psychological Science (APS) is another association to which many I/O psychologists belong.

Those who work in the I/O field may be based at a university, teaching and researching I/O-related topics. Some private organizations employing I/O psychologists include DDI, HUMRRO, Corporate Executive Board (CEB), and IBM Smarter Workforce. These organizations engage in services such as testing, performance management, and administering attitude surveys. Many organizations also hire in-house employees with expertise in I/O psychology–related fields to work in departments including human resource management or “people analytics.” According to a 2011 membership survey of SIOP, the largest percentage of members were employed in academic institutions, followed by those in consulting or independent practice, private sector organizations, and public sector organizations (Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 2011). Moreover, the majority of respondents (86%) were not licensed.

Since then, thousands of articles have been published on topics relating to I/O psychology, and it is one of the influential subdimensions of psychology. I/O psychologists generate scholarly knowledge and have a role in recruitment, selection, assessment and development of talent, and design and improvement of the workplace. One of the major projects I/O psychologists contributed to is O*Net, a vast database of occupational information sponsored by the U.S. government, which contains information on hundreds of jobs, listing tasks, knowledge, skill, and ability requirements of jobs, work activities, contexts under which work is performed, as well as personality and values that are critical to effectiveness on those jobs. This database is free and a useful resource for students, job seekers, and HR professionals.

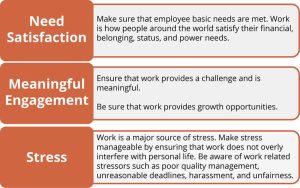

Findings of I/O psychology have the potential to contribute to the health and happiness of people around the world. When people are asked how happy they are with their lives, their feelings about the work domain are a big part of how they answer this question. I/O psychology research uncovers the secrets of a happy workplace (Figure 11). Organizations designed around these principles will see direct benefits, in the form of employee happiness, well-being, motivation, effectiveness, and retention.

Conclusion

We have now reviewed what I/O psychology is, what I/O psychologists do, the history of I/O, associations related to I/O psychology, and accomplishments of I/O psychologists. Those interested in finding out more about I/O psychology are encouraged to visit the outside resources below to learn more.

Outside Resources

Careers: Occupational information via O*Net\’s database containing information on hundreds of standardized and occupation-specific descriptors http://www.onetonline.org/

Organization: Society for Industrial/Organizational Psychology (SIOP) http://www.siop.org

Organization: Alliance for Organizational Psychology (AOP) http://www.allianceorgpsych.org

Organization: American Psychological Association (APA) http://www.apa.org

Organization: Association for Psychological Science (APS) http://www.psychologicalscience.org/

Organization: European Association of Work and Organizational Psychology (EAWOP) http://www.eawop.org

Organization: International Association for Applied Psychology (IAAP) http://www.iaapsy.org/division1/

Training: For more about graduate training programs in I/O psychology and related fields http://www.siop.org/gtp/

Discussion Questions

- If your organization is approached by a company stating that it has an excellent training program in leadership, how would you assess if the program is good or not? What information would you seek before making a decision?

- After reading this module, what topics in I/O psychology seemed most interesting to you?

- How would an I/O psychologist go about establishing whether a selection test is better than an alternative?

- What would be the advantages and downsides of pursuing a career in I/O psychology?

Vocabulary

- Hawthorne Effect An effect in which individuals change or improve some facet of their behavior as a result of their awareness of being observed.

- Hawthorne Studies A series of well-known studies conducted under the leadership of Harvard University researchers, which changed the perspective of scholars and practitioners about the role of human psychology in relation to work behavior.

- Industrial/Organizational psychology Scientific study of behavior in organizational settings and the application of psychology to understand work behavior.

- O*Net A vast database of occupational information containing data on hundreds of jobs.

- Scientist-practitioner model The dual focus of I/O psychology, which entails practical questions motivating scientific inquiry to generate knowledge about the work-person interface and the practitioner side applying this scientific knowledge to organizational problems.

- Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology (SIOP) A professional organization bringing together academics and practitioners who work in I/O psychology and related areas. It is Division 14 of the American Psychological Association (APA).

- Work and organizational psychology Preferred name for I/O psychology in Europe.

References

American Psychological Association. (2011). Psychology job forecast: Partly sunny. Retrieved on 1/25/2013 from http://www.apa.org/gradpsych/2011/03/cover-sunny.aspx

Briner, R. B., & Rousseau, D. M. (2011). Evidence-based I-O psychology: Not there yet. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 4, 3–22.

Erdogan, B., Bauer, T. N., Truxillo, D. M., & Mansfield, L. R. (2012). Whistle while you work: A review of the life satisfaction literature. Journal of Management, 38, 1038–1083.

Industrial/Organizational (I/O) Psychology by Berrin Erdogan and Talya N. Bauer is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available in our Licensing Agreement.

Koppes, L. L. (1997). American female pioneers of industrial and organizational psychology during the early years. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82, 500–515.

Landy, F. J. (1997). Early influences on the development of industrial and organizational psychology. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82, 467–477.

Manjoo, F. (2013). The happiness machine: How Google became such a great place to work. Retrieved on 2/1/2013 from http://www.slate.com/articles/technology/technology/2013/01/google_people_operations_the_secrets_of_the_world_s_most_scientific_human.html

Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology. (2011). SIOP 2011 membership survey, employment setting report. Retrieved on 2/5/2013 from http://www.siop.org/userfiles/image/2011MemberSurvey/Employment_Setting_Report.pdf

U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2011). Economic news release. Retrieved on 1/20/2013 from http://www.bls.gov/news.release/atus.t04.htm